Manuscript

Leveraging Human Factors Engineering to Optimize Drug Checking Tools

Optimizing Drug Checking Tools through HFE

Annastasia R. Beal¹, Bryce Batcheller²†*

¹Harm Reduction Circle, Irvine, California, USA; ²WiseBatch LLC, Costa Mesa, California, USA.

*Corresponding author: annastasia@harmreductioncircle.org

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

Leveraging Human Factors Engineering to Optimize Drug Checking Tools

Abstract

Accurate, user-friendly drug checking tools are critical in reducing overdose risks, especially in settings where people test substances without professional guidance. This study examined whether a small design change—a 10mg micro scoop—could improve how users interact with fentanyl test kits. During a multi-day music festival, 50 participants were randomly assigned to use one of two test kits: one with the scoop (Version A) and one without it (Version B). Each person used written instructions only and completed a survey afterward. Participants using the scoop-equipped kit achieved 100% accuracy when interpreting results, compared to 84% accuracy in the group without the scoop. They also rated the instructions as clearer—91% versus 73%—and reported feeling more confident and less confused during testing. Many described the scoop as helpful in measuring and mixing the sample. These findings show that even simple, user-centered design improvements can make drug checking more effective and accessible in real-world environments. Improving ease of use may increase the reliability and impact of harm reduction tools in preventing overdose.

Keywords: fentanyl test strips; drug checking; harm reduction; human factors engineering; usability study; overdose prevention; user-centered design; substance use; testing kits; festival safety;

Subject Classification Codes: Health and Safety (e.g., 62P10, 62M30); Public Health (e.g., 91C44); Addiction and Substance Use (e.g., 92E70); Human Factors and Ergonomics (e.g., 94C37).

Introduction

The overdose crisis and recreational drug contamination

The ongoing opioid overdose crisis represents a significant public health challenge, exacerbated by the increasing contamination of non-opioid recreational drugs with fentanyl—a potent synthetic opioid linked to numerous accidental overdoses and fatalities [1,2]. This phenomenon has profoundly impacted communities and individuals engaging in recreational substance use, especially in environments such as nightlife events and music festivals, where substance use is prevalent and individuals may have limited knowledge or preparedness regarding opioid exposure risks [3,4,5].

The Role and Limitations of Fentanyl Test Strips

Drug checking has emerged as an essential harm reduction intervention aimed at mitigating these risks. Among available drug checking tools, fentanyl test strips (FTS) are recognized for their cost-effectiveness, portability, and ability to rapidly detect the presence of fentanyl in drug samples [1,6]. While FTS have seen growing acceptance within syringe service programs [6,7], their effective deployment in broader recreational settings has been hampered by usability challenges and variable levels of user understanding and confidence [7,8]. Specifically, the clarity of instructions, ease of use, and users' confidence in interpreting results remain inconsistent, leading to potential misuse and undermining the overall effectiveness of these crucial harm reduction tools.

Human-Centered Design and Harm Reduction Technology

Human Factors Engineering (HFE) provides a robust framework for addressing these usability challenges by focusing explicitly on user-centered design principles, improving tool accessibility, and minimizing user error in high-stimulation, real-world environments [9]. Research consistently demonstrates that harm reduction tools designed using human-centered principles significantly enhance user experience, comprehension, and performance, especially in settings where immediate professional guidance is unavailable [4].

Study Objective and Design Overview

This study seeks to apply HFE principles to improve the usability and effectiveness of fentanyl test strips through the integration of a standardized micro scoop as a dosing aid. Specifically, our research addresses the question: Does the inclusion of a simple design enhancement (a standardized 10mg micro scoop) significantly impact the accuracy of test result interpretation, clarity of instructions, and user confidence among festival attendees performing drug checking independently?

By evaluating two prototype fentanyl test kits—one incorporating the micro scoop (Version A) and one without this enhancement (Version B)—this randomized usability study, conducted in partnership between Harm Reduction Circle and WiseBatch LLC, aims to provide critical insights into how minor, user-centered design modifications can significantly improve real-world outcomes. The findings of this study have direct implications for enhancing the effectiveness of harm reduction practices and potentially reducing overdose incidents in recreational drug-using populations.

Methods

Experimental Design

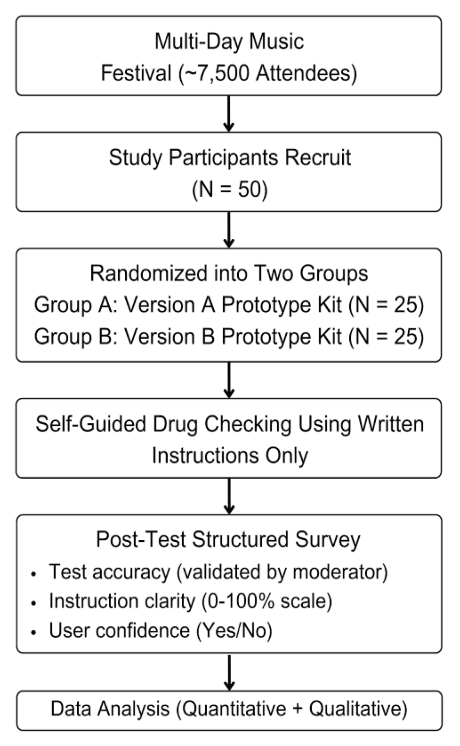

The objective of this study was to evaluate and compare the usability and accuracy of two drug checking prototype kits (Version A and Version B) among a diverse group of potential end-users. The study utilized a randomized usability design with prespecified components to ensure replicability and validity.extract.

50 participants were recruited from the Same Same But Different Music Festival, held from September 27-29, 2024, in Perris, CA 92571. This setting provided access to a large and diverse population of potential end-users, and participants were selected to reflect a range of real-world users, including harm reduction practitioners and people who use drugs (PWUD), with and without prior experience using drug checking tools.

Participants were randomly assigned to test either Version A or Version B of the prototype drug checking kits. Each participant independently performed drug checking using a simulated drug sample provided by the study team, relying solely on written instructions included with their assigned kit. No verbal guidance was offered to participants, simulating realistic conditions wherein users typically perform drug checking without external support.

Figure 1: A diagram illustrating the study design, from participant recruitment through data collection and final analysis.

Procedures

After completing the drug checking procedure, participants completed a structured survey designed to assess both quantitative and qualitative outcomes. The survey measured:

Accuracy of test result interpretation

Clarity of instructions, rated on a 0% to 100% scale

Confidence in correct use (Yes or No)

Difficulties encountered / Suggested improvements

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data analysis included calculating the overall accuracy rates and mean clarity scores for each prototype kit version. Confidence in correct usage was summarized using descriptive statistics. Qualitative feedback was reviewed and analyzed thematically to identify recurring challenges and usability concerns.

Statistical significance was assessed using appropriate methods, including chi-square tests for categorical variables (e.g., accuracy, confidence levels) and independent t-tests for continuous variables (e.g., clarity scores). The values for N, P, and the specific tests performed are noted in the figure legends or described in the main text.

Results

Human-Centered design Improved Usability and Performance

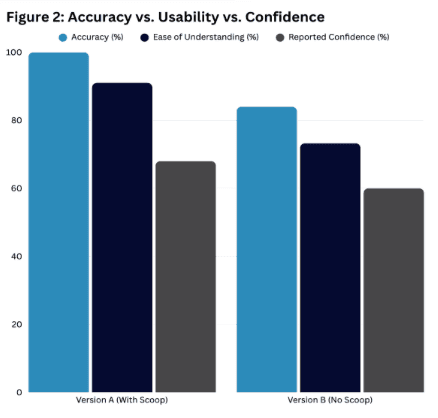

The randomized usability study revealed significant differences in accuracy, instruction clarity, and user confidence between two drug checking kit prototypes. Participants using Version A, which included a 10mg micro scoop, outperformed those using Version B, which lacked a scoop. Of the 50 total participants, those assigned to Version A (n = 25) achieved a 100% correct interpretation rate, compared to an 84% correct interpretation rate among participants assigned to Version B (n = 25). These results suggest that the addition of a micro scoop contributed to better dosing accuracy and interpretation, reducing variability in user behavior.

Clarity of Instructions Varied Between Test Kits

Participants using Version A reported a higher average instruction clarity score (91.0%) compared to those using Version B (73.25%). Feedback indicated that the scoop helped standardize the amount of sample used, contributing to a smoother, more intuitive testing experience. Users of Version A described the instructions as clear and easy to follow, with minimal confusion. In contrast, Version B participants frequently cited vague or ambiguous phrases—such as “crush or mix”—as contributing to confusion and hesitation. Several participants in the Version B group recommended more visual guidance and explicit sample preparation instructions.

User Confidence Aligned with Test Kit Design

Participants using Version A overwhelmingly reported confidence in their ability to correctly use the kit, aligning with their high accuracy scores and clarity ratings. In contrast, users of Version B expressed greater uncertainty, often noting a lack of instruction on how much sample to use. Many indicated that the absence of a dosing guide contributed to a feeling of guesswork, which negatively impacted their overall confidence in the results.

Quantitative Results for Version A: Test Kit with 10mg Micro Scoop

The scoop made the process intuitive and standardized

Instructions were clear; minimal confusion reported

High user confidence in performing the test independently

Quantitative Results for Version B: Standard Test Kit Without Scoop

Common Feedback:

The Confusion by unclear language (e.g., “crush or mix”)

No guidance on sample quantity/dose

Lower user confidence and frequent hesitation

Suggestions included improved visual instructions

Figure 2: Bar charts illustrating the study design, from a comparative breakdown of participant accuracy and clarity scores between Version A and Version B.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that small-scale, human-centered design interventions—such as the inclusion of a 10mg micro scoop—can meaningfully improve the usability, accuracy, and user confidence associated with drug checking technologies. Among a diverse sample of music festival attendees, participants using Version A of the test kit exhibited higher accuracy and reported greater clarity and confidence when compared to those using Version B, which lacked a dosing scoop. These results illustrate the practical value of intuitive, standardized components in the design of harm reduction tools.

The findings underscore how simple, low-cost design features can address common barriers to proper drug checking, particularly in real-world settings where users may have limited instruction or support. Participants emphasized that the scoop eliminated guesswork about sample size, reducing anxiety and improving the overall user experience. These results support previous literature highlighting the effectiveness of user-informed product design, especially among people who use drugs (PWUD) and others navigating low-resource or high-stress environments.

In contrast, the relatively lower performance of Version B highlights the risks of vague instructions and a lack of dosing guidance. Participant feedback revealed that even slight ambiguities in phrasing—such as “crush or mix”—introduced uncertainty and impacted confidence in the results. These usability challenges reinforce existing evidence that clarity, simplicity, and standardization are essential design considerations, particularly for first-time users or those with limited literacy or health literacy.

The broader implications of these findings are especially relevant to public health and procurement professionals. As drug checking tools become more widely adopted, it is imperative that developers and decision-makers prioritize participatory design methods that actively engage end-users and harm reduction practitioners. Embedding usability testing and user feedback loops into development processes can improve adoption, reduce misuse, and maximize the impact of these life-saving interventions.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study was conducted in a single field setting—an outdoor music festival attended by approximately 7,500 guests. While this context provides access to a diverse pool of potential users, results may not be generalizable to all settings, such as syringe service programs, unsheltered encampments, or individuals who use drugs in isolation. Additionally, the simulated drug samples used during testing were designed for consistency and safety but may not fully reflect the complexity or variability of substances found in real-world use.

Future research should examine how human-centered design modifications perform across other use environments, including underserved or rural communities, and among individuals with low literacy or limited English proficiency. Longer-term studies should also assess whether improvements in usability and confidence translate to increased engagement with drug checking services, improved overdose prevention behaviors, and reduced harm.

By demonstrating that strategic, low-cost enhancements can drive meaningful improvements in drug checking outcomes, this study contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting innovation through harm reduction. Future product development should continue to center the lived experiences of those most impacted by the overdose crisis.text.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. As no personally identifiable information was collected, the study was exempt from the requirement for Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study. Participants were fully informed of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Participation was voluntary, and participants were given the option to withdraw at any time without penalty.

The data collected were anonymous and consisted solely of responses to structured surveys. All responses were stored securely, and no personally identifiable information was recorded or maintained. The study was designed to minimize any potential risks to participants, ensuring that no harm would come from their involvement.

The research team adhered to ethical guidelines for the protection of human subjects and conducted the study with full respect for participants' rights and dignity.

Data Availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are presented within the main text and Supplementary Materials. No additional datasets were generated or analyzed.

Funding

The authors acknowledge that they did not receive funding for this work. The study was conducted as part of the independent research and outreach efforts of Harm Reduction Circle and WiseBatch LLC.

Authors' Contributions

B.B. conceptualized the study and provided oversight of the overall experimental design. A.R.B. drafted the study framework, led outreach coordination, and leveraged community networks to secure the opportunity to conduct the research. Both A.R.B. and B.B. jointly conducted data collection and collaborated on analysis and interpretation of the results. A.R.B. led manuscript writing and provided strategic support on harm reduction protocols, promotion, participant recruitment, and engagement throughout the study. B.B. developed the prototype kits, designed the visuals and instructions included with both versions of the packaging, and provided technical oversight. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article. WiseBatch LLC is named in the study as a collaborator but did not influence the study’s analysis, interpretation, or decision to publish.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to Danny Korra with Lighthouse Medical Services for permitting the study to take place, along with the entire medical team at the Same Same But Different Music Festival 2024 (SSBD). We also thank the co-founders of SSBD, Brad Sweet and Peter Eichar, for their continued invitation to Harm Reduction Circle to engage with their event community, enabling the collection of data during the 2024 festival. This work was made possible through a collaborative effort between WiseBatch LLC, who provided logistical expertise and technical support related to drug checking protocols, and the countless on-site volunteers from Harm Reduction Circle, whose efforts were essential to participant coordination and field execution. We further acknowledge Harm Reduction Circle for applying user-centered design principles and human factors engineering to optimize study implementation. Finally, we are deeply grateful to the 50 participants who contributed their time, insight, and lived experience in service of advancing harm reduction research.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Participant-Level Results by Test Kit Version

Each row represents an individual participant’s responses and test outcome across eight measured variables.

User ID | Version (A/B) | Stated Result | Correct (Y/N) | Reported Confidence (Y/N) | Encountered Issues | Suggested Improvements | Instruction Clarity Score (%) |

1 | B | Negative | Yes | Yes | Clear Lines | 100% | |

2 | A | Negative | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

3 | A | Negative | Yes | Yes | Longer then need explaining | A simple quick what to do then a more complex discretion | 60% |

4 | B | Negative | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

5 | A | Positive | Yes | No | 80% | ||

6 | A | Negative | Yes | Yes | suggests the instructions have bullet points | Loves the scoop and bullet points | 60% |

7 | B | Negative | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

8 | B | Negative | No | Yes | 20% | ||

9 | A | Positive | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

10 | A | Negative | Yes | Yes | Familiar with WiseBatch strips in Reno Nevada | 100% | |

11 | A | Negative | Yes | No | Familiar with WiseBatch strips in Reno Nevada | 100% | |

12 | B | Negative | Yes | No | 40% | ||

13 | A | Positive | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

14 | A | Negative | Yes | Yes | 80% | ||

15 | A | Negative | Yes | Yes | Confused about block in bottle | Say how long to leave in the strip | 80% |

16 | A | Negative | Yes | No | 80% | ||

17 | B | Negative | Yes | Yes | 60% | ||

18 | A | Positive | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

19 | B | Negative | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

20 | A | Positive | Yes | Yes | 80% | ||

21 | B | Negative | Yes | No | 80% | ||

22 | A | Negative | Yes | No | Mix the substance well, more information about that | More information about mixing | 100% |

23 | A | Negative | Yes | No | 100% | ||

24 | A | Negative | Yes | No | No feedback, test strip in this pouch for separate pouch | 100% | |

25 | B | Negative | Yes | Yes | 60% | ||

26 | A | Positive | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

27 | B | Negative | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

28 | A | Positive | Yes | No | Confused about Fentanyl vs Covid Test | Clarify 'crush or mix' for first-timers | 100% |

29 | A | Positive | Yes | No | No feedback, test strip color orientation | 100% | |

30 | A | Positive | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

31 | A | Positive | Yes | Yes | Got WiseBatch strips in Reno Nevada | 100% | |

32 | B | Positive | Yes | No | Quarter shot was a little confusing | Quarter shot confusing | 100% |

33 | B | Negative | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

34 | A | Positive | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

35 | B | Negative | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

36 | A | Positive | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

37 | B | Positive | Yes | Yes | Misread instructions, confusing at first | Numbered instructions; remove strip from water instead of remove strip | 40% |

38 | B | Negative | No | Yes | More distinct labeling | 60% | |

39 | B | Negative | Yes | No | “Crush or mix” misunderstood | Crush or mix misunderstood | 80% |

40 | B | Positive | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

41 | B | Positive | Yes | No | Concern about not always having a cup | 100% | |

42 | B | Positive | Yes | No | 100% | ||

43 | A | Positive | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

44 | B | Positive | Yes | No | 80% | ||

45 | B | Positive | Yes | No | 80% | ||

46 | A | Negative | Yes | Yes | 100% | ||

47 | B | Negative | No | Yes | ‘Strip’ confusing | ‘Strip’ confusing | 80% |

48 | B | Positive | Yes | Yes | No feedback, appreciated the max line picture | Appreciated the max line picture | 100% |

49 | B | Negative | No | Yes | 40% | ||

50 | B | Positive | Yes | Yes | Less words, more colors | More colors to draw the eye | 100% |

References

[1] Tupper KW, McCrae K, Garber I, Lysyshyn M, Wood E. Initial results of a drug checking pilot program to detect fentanyl adulteration in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;190:242–245. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.020

[2] Bardwell G, Kerr T. Drug checking: A potential solution to the opioid overdose crisis? Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2018;13(1):1–3. doi:10.1186/s13011-018-0156-3

[3] McDonald R, Strang J. Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction. 2016;111(7):1177–1187. doi:10.1111/add.13326

[4] Nicholas C. Peiper, Sarah Duhart Clarke, Louise B. Vincent, Dan Ciccarone, Alex H. Kral, Jon E. Zibbell. Fentanyl test strips as an opioid overdose prevention strategy: Findings from a syringe services program in the Southeastern United States. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.08.007

[5] International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC). Drug Checking as a Harm Reduction Intervention: Evidence, Best Practices and Challenges. Published November 2022. Accessed April 6, 2025. https://idpc.net/publications/2022/11/drug-checking-as-a-harm-reduction-intervention-evidence-best-practices-and-challenges

[6] Sherman SG, Green TC, Glick J, et al. Acceptability of implementing community-based drug checking services for people who use drugs in three United States cities: Baltimore, Boston and Providence. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.003

[7] Krieger MS, Goedel WC, Buxton JA, Lysyshyn M, Bernstein E, Sherman SG, Rich JD, Hadland SE, Green TC, Marshall BDL. Use of rapid fentanyl test strips among young adults who use drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;61:52–58. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.09.009

[8] World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines on Developing Consumer Information on Proper Use of Medicines. Published 2004. Accessed April 6, 2025. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241591692

[9] Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Human Factors and Usability Engineering – Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff. Published 2021. Accessed April 6, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/media/80481/download